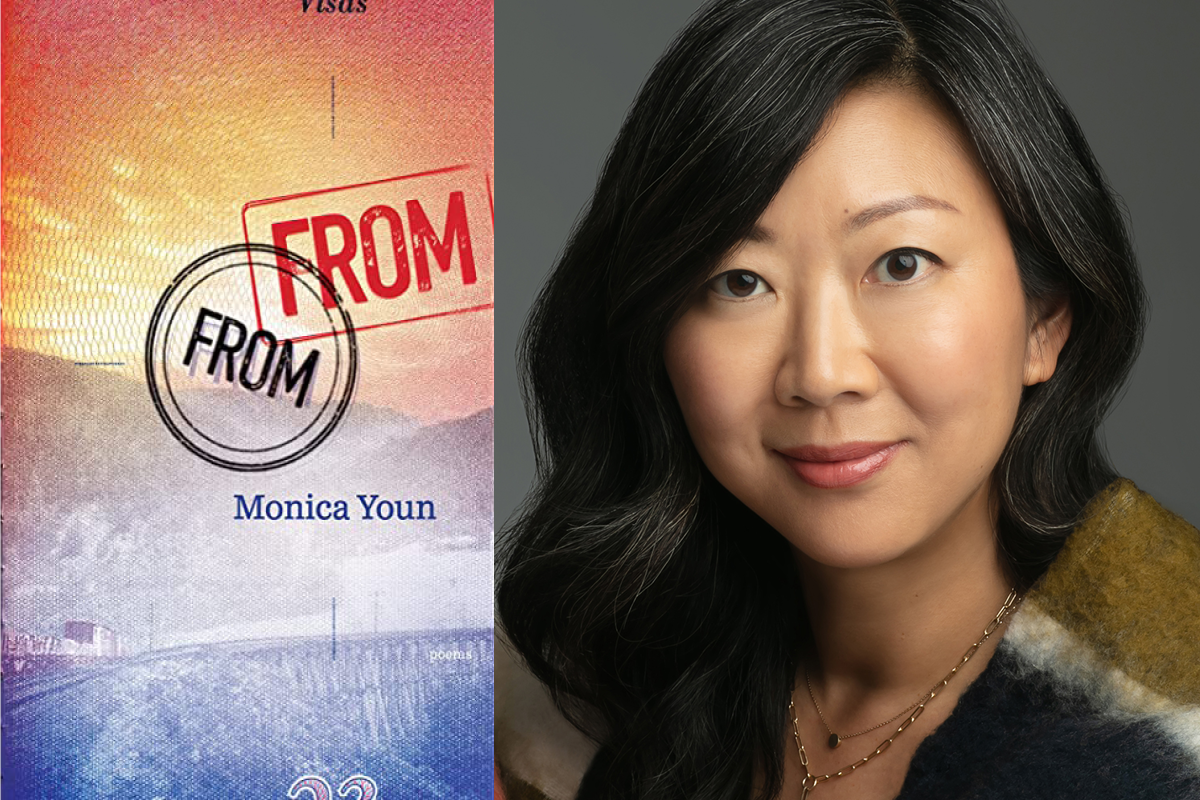

7 Moving Moments in From From by Monica Youn

Racism, absurdity, and fantasy converge in this staggering new poetry collection from Monica Youn. Published March 7, 2023, From From is Youn’s fourth collection. Among a number of accolades for her writing, the lawyer-turned-poet was a finalist for the 2010 National Book Award in Poetry for her second collection, Ignatz, and was later longlisted for the 2016 National Book Award for Poetry with her debut collection, Blackacre. From From was a highly anticipated release this year, and we’ve selected seven thought-provoking moments to commemorate from the collection.

1. It interrogates the concept of “home.”

The book opens with a quote from artist Paul Chan: “Is there a direction home that doesn’t point backward?” From here, readers fall into the collection with a destabilized sense of direction. Where is home? Is it found or invented? And by whom?

2. It deconstructs “authenticity.”

Much like the concept of home, the concept of authenticity is a moving target in From From. The poem “Canon” (43) considers the commodification of “Asianness for Western Consumption.” While the speaker of the poem participates with their Asian heritage in numerous ways, they are also caught off guard by the possibility that their very concept of Asianness has been manufactured in a Western environment.

3. It calls existing a political act.

“Revealing a racial marker in a poem is like revealing a gun in a story or like revealing a nipple in a dance” (3), says the narrator in the opening poem of the collection. “After such a revelation, the poem is about race, the story is about the gun…” When race is something that may be readily identified outside of a person’s body, in what ways might their existence be defined?

4. It considers how spaces are defined and who can access them.

In the poem “Study of Two Figures (Pasiphae/Sado),” the narrator describes two figures preserved inside containers. “Both containers allow the tourist and the artist to touch the hot button, the taboo. / The desire and the discomfort are contained. / Both containers allow the tourist and the artist to walk away. / The male and female figures remain contained” (6). While the races of the tourist and the artist in this poem are undefined, the races of the two figures are. In what ways can race become a container? And who has the privilege to move in and out of those containers? Why?

5. It stretches the meaning of the word “magpie” to new lengths.

Section four of the collection is titled “The Magpies.” In the notes section (45), Youn explains that in many Asian countries, the magpie symbolizes good news, while in most European traditions, it is considered a thief or a bad luck omen. This two-sided symbol becomes a vehicle for understanding submission, repression, fear, and desire.

6. It studies the power of passive voice.

Often used to create general ambiguity for the sake of politeness or evasiveness, the passive voice is a sentence construction in which the subject receives the action, rather than performing it. “The ball was thrown,” for example, is in the passive voice. Section five is titled “In the Passive Voice,” to interrogate this construction and how it is used by those with and without power to both create and avoid conflict.

7. Its notes section is as illuminating as the poems themselves.

The notes section is nothing to skip in this collection. Notes on many of the poems and their recurring image and themes provide further insights into Youn’s inspirations and motives behind each poem. They also provide a glimpse into the research that went into making this extraordinary collection.