In 2020 National Book Award Winner DMZ Colony, Don Mee Choi Breaks Down Barriers

Poet Layli Long Soldier announced DMZ Colony by Don Mee Choi (Wave Books) as the winner of the 2020 National Book Award for Poetry during a ceremony held virtually due to the pandemic. DMZ Colony was a finalist among works by Mei-mei Berssenbrugge, Tommye Blount, Anthony Cody, and Natalie Diaz. Choi is also the author of Hardly War (Wave Books, 2016), The Morning News Is Exciting (Action Books, 2010), and many other chapbooks and essays. She has translated several of Kim Hyesoon’s poetry collections, including Autobiography of Death, which received the 2019 International Griffin Poetry Prize.

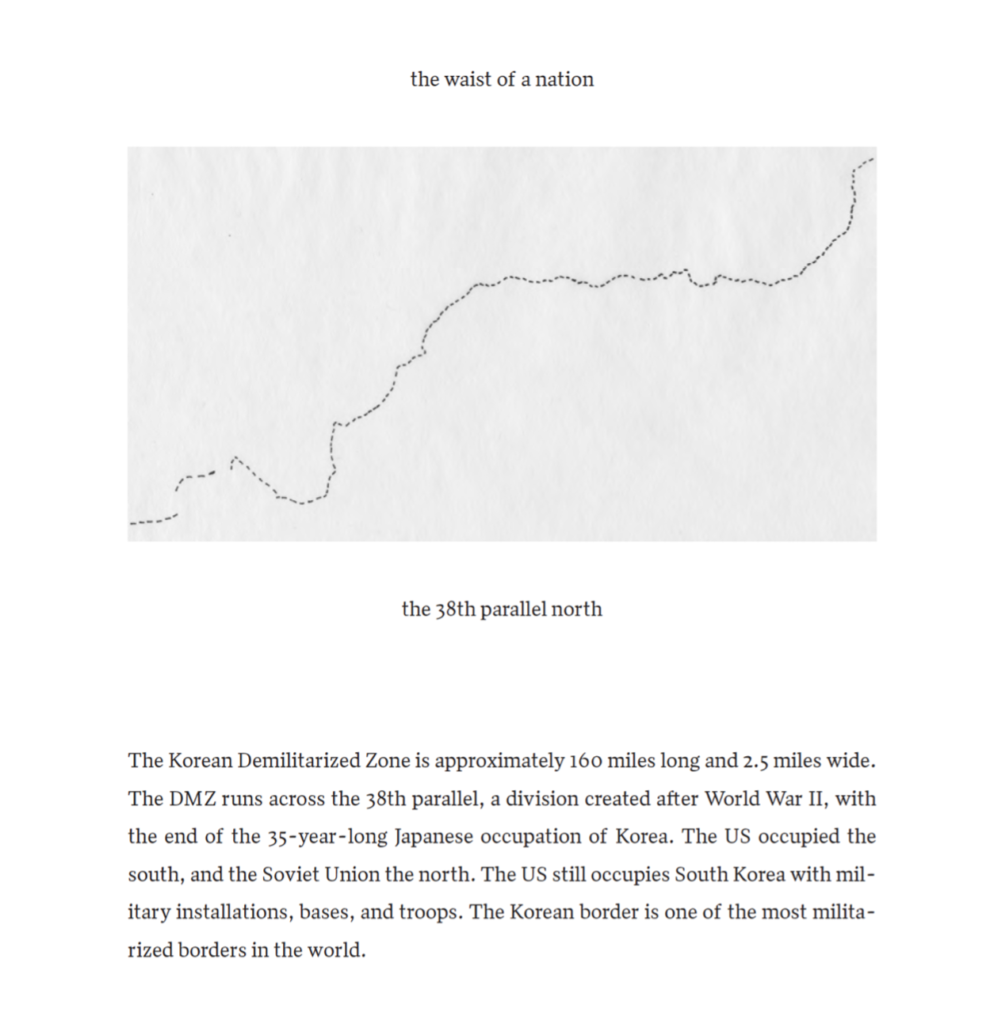

Don Mee Choi grew up in South Korea during General Park Chung Hee’s rise to power, and in 1972—at the age of 10—she and her family relocated to Hong Kong. The “DMZ” in DMZ Colony is the shorthand term for the “Demilitarized Zone,” explained on page 5:

DMZ Colony features a tapestry of perspectives, separated into chapters: SKY TRANSLATION sets up the project; WINGS OF RETURN includes Choi’s personal history in Korea as well as first-hand accounts from Mr. Ahn Hak-sǒp, a man who survived over 40 years of political imprisonment and torture; PLANETARY TRANSLATION holds drawings and thoughts from a conversation with activist Ahn-Kim Jeong-Ae; THE ORPHANS showcases translations of stories written by young girls surviving South Korea’s Sancheong-Hamyang massacre in 1951; THE APPARATUS experiments with collage using theory and philosophy; INTERPELLATION OF RETURN unravels misconceptions about Korean history using translation, artifact, and “bricolage,” or “an imaginary assemblage”; MIRROR WORDS collages words and images which are, as she describes, a product of translation as an anti-neocolonial mode; and (NEO) (=) ANGELS pairs poems with images from her war photographer father’s archive.

Each of these chapters, when not first-person from Choi, read like found poems. As she says on page 49, “. . . language—that is to say translation—always arises from collective consciousness,” which explains why the words and images collaged to show what the world was and is like for those affected by the Demilitarized Zone works so well. Choi is able to use lots of roles to tell a collective history and, most importantly, the truth within it. She’s part-historian, part-interviewer, part-translator, part-anthropologist, part-diarist and all poet.

DMZ Colony is so important for the America where we live now because, among other things, it aims to locate where politics take a turn: what causes someone to reject compassion and humanity and, instead, support systems of oppression and lack of empathy? In a time where many Americans use politics to justify excluding others and upholding insidious narratives, this book is a poetic reminder of how history can go, a collage of how we’re all connected, a way of passing through a border instead of around or alongside.

These stories are needed, written down and shared, to make known what happened to these humans: the faces, souls, and lives behind words like “border,” “massacre,” and “war prisoner.” The emphasis here is on human; we need to see the humanity amidst the brutality and awful details. We need to know their truths before they become hidden again, and DMZ Colony serves as a record to ensure their lasting power. As Don Mee Choi says in the acknowledgements: “Poetry is more effective as a language of resistance. Poetry can defy erasure.”