Jenna Clare Talks Creative Process and Poetry as Activism

“If a reader can walk away thinking, “Wow the world really has to change,” that’s enough.”

Jenna Clare is an artist of multiple disciplines and author of the poetry collection Water Runs Red. Writing a collection of poetry is a daunting task, but this young writer did more than just sit down for a year or two and write her heart out.

From photography and graphic design to writing and videography, Jenna Clare laid out a masterful body of work in her self-published collection. She even found time to make a documentary, journalling her creative process.

I watched the documentary before speaking with Jenna about the journey that she went on to complete Water Runs Red and found a deeper understanding of her creative process.

Shon Houston: Can you give readers an idea of the journey they will go on while reading your first book Water Runs Red, or do you prefer to leave it up to the readers’ interpretations?

Jenna Clare: Even though I fully believe that poetry collections are subjective and up to interpretation, I love telling people what to expect with my book because it’s so universally relatable.

I believe this is a journey that almost everyone has gone through, so even if the reader will never fully understand my own experience, they will probably be able to relate it to their own life fairly easily—or at least some parts of the narrative.

The journey of this book is all about finding light in the middle of darkness. I wanted to focus on “bad blood” and different kinds of feuding, both external and internal, so even though I like to say this book is about toxic friendships, it also highlights the feuds we have in our own brains and the feuds we have with the world around us.

In short, the reader will go on the same journey I’ve been traveling for the past five to ten years of my life. Hopefully, by the end of it, they will see a light at the end of the tunnel as I did.

SH: How do you connect with your audience through the art you create?

JC: You may not know this about me based on the art I share online, but I’m a very private person.

I’m a five on the Enneagram, which means I’m pretty closed off, and I don’t share a lot of my emotions or thoughts in person. However, because I’m such an artistic soul, I actually love getting to express myself through my art and sharing that art with other people. So the art I create allows me to connect with people very deeply because that’s one of the few ways I feel like I can share pieces of myself.

The art I create has always given me the opportunities to create lasting relationships, and without sharing my photos or songs or YouTube videos online, I think I would lack some vital connections to the world.

SH: Do you see Water Runs Red as being a standalone book or will there be a series?

JC: No matter how well this book does, I never saw it as part of a series. This is one story that I wanted to tell, and I don’t need to add anything on to it.

I know that can be upsetting because so much of us love getting sequels, but there’s something poignant about it being standalone, and I don’t want to mess that up. More than that, I don’t think I have it in me to format another poetry collection like this. Two and a half months of 5-10 hour days working on Photoshop is enough for one lifetime!

SH: It’s clear that being a multi-disciplined artist played a big part in Water Runs Red. What was your process like, and how did you stay organized?

JC: While I was working on the art aspect of this book I kind of felt like I was going mad—my process was very elaborate and tedious, and it involved hundreds of files and Photoshop layers.

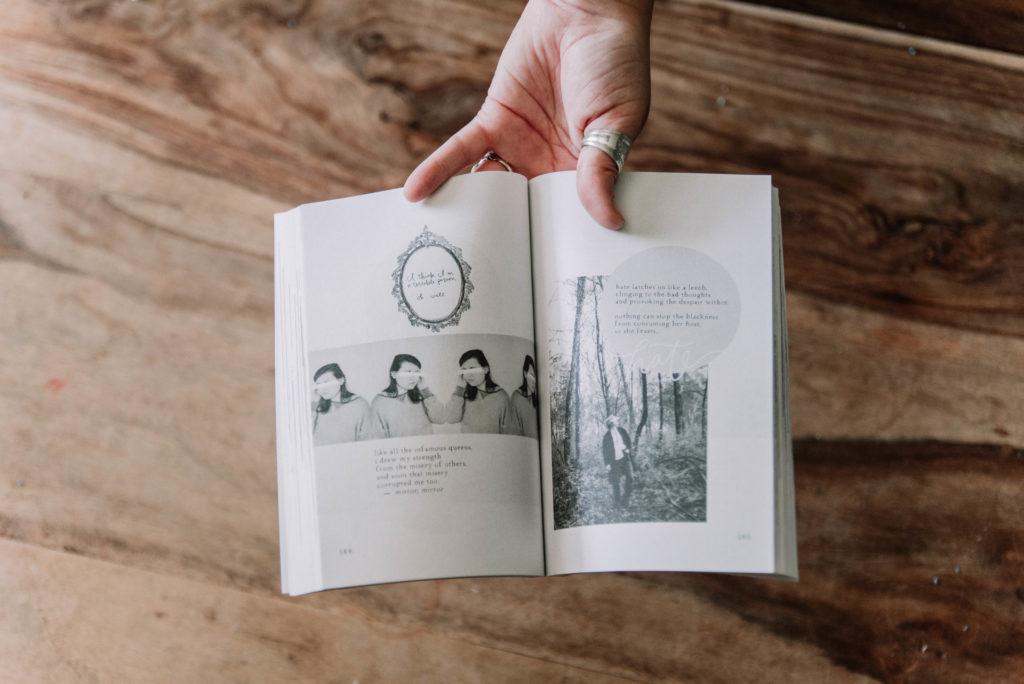

I made a whole documentary to show how I actually created each page because I did create all 300 pages individually in Photoshop, but in short, I added photos, text, hand lettering, and a lot of doodling, all in a way that made the book feel like a journal.

I wanted it to be personal and artsy, but also kind of childish as if you were reading a high schooler’s scrapbook. I used photos from literally my entire life—some are old family photos, some I took in middle school with my old point & shoot camera, and a lot are from college/post-grad.

As someone who has done these types of intense digital art projects in the past, I didn’t have an issue with staying organized, but sometimes when I think about it all from an outsider’s perspective…I really don’t know how I did all of it!

SH: I read that you utilized beta-readers to help you through the first rounds of editing Water Runs Red. What advice do you have for writers who are not as connected in the community but are looking for help with editing their first work?

JC: It can be hard when you aren’t a part of the community to find people to help you, whether that’s networking to get into a big publisher or just finding friends to support you, but my best advice for those people is to join the community!

A lot of independent authors or writers who are just starting to get into publishing seem to think that you need to spend money to sell your book or to become published, and that’s just not true.

I know it can be intimidating at first, but [I like to] think of it more as making friends than finding contacts. If you create genuine relationships with people who are looking to do the same thing you are—write a book, work in publishing, etc.—you will definitely find people who can help support you. If you don’t know where to look or how to do that, hop on Twitter or Bookstagram or Goodreads!

More than that, you don’t [always] need to hire some big-time fancy editor to dramatically change your writing. Even if you find people who like the kind of book you’re [working on], those not-so-professional readers can be a big help in pointing out the glaring flaws in your writing.

Sometimes the first step to making a major edit isn’t someone telling you to add a comma or fix your punctuation, it’s actually a casual Instagram follower who tells you that they didn’t understand to whom a poem was referring.

Most of my beta-readers were friends of mine that I trust dearly, but I also enlisted a few strangers to help bridge the gaps and give me the honesty I needed. Beta-readers are very important to editing, and they can only help you going forward, especially if you’re still in the early drafting stages and you can’t afford to hire an editor.

SH: Reading your collection, I felt the harmony between your words, your imagery, and your music. Did you develop this multifaceted experience over time or was it the plan all along to pair your words with other mediums?

JC: Thank you! I worked incredibly hard on creating that harmony. From the beginning, I didn’t actually know it was going to turn into this mixed-medium book. I had originally planned on adding doodles to most of the pages like any other poetry book, but when I was finally starting to plan the formatting, I decided that I wanted to stand out and create something that made the reader stay on the page for more than a few lines.

I love contemporary poetry books, but it seemed wasteful to me that some of the pages in those books are so bare and empty. It wasn’t until about eight months into the project that I actually decided that I wanted to create this scrapbook/journal art, but it felt so natural because I have a lot of photographs in my archive, and I’ve always been known for my journaling skills. Even though the art was difficult, it was harder to make sure the words and poems flowed seamlessly.

To get the harmony you mentioned, I worked for about a year to make sure everything transitioned smoothly. And the more I edited, the more hidden easter eggs I added to the book as well. As someone who loves all types of media, I really wanted to find a way to incorporate my favorite things into this book that is so intensely ME! (Taylor Swift anyone?)

I didn’t want it to be something so obvious as stating which songs inspired me or something so vague as saying a poem was inspired by a certain movie, so I decided to hide references throughout the book. In the back of my head, I had always wanted it to be multifaceted and complex, but it wasn’t until I got some help from my beta-readers that I figured out how to do it. And it was a lot of work, but, in the end, I’m so proud of how harmonic it became!

SH: People always ask writers which authors influence their work. What are some of the less conventional influences for your writing?

JC: Many contemporary poets use other poets or authors as inspiration for their work, and while I love people like Sophia Elaine Hanson or Amanda Lovelace, my poetry is most heavily influenced by musicians and songwriters.

For instance, the band AJR is doing incredible things in the music industry right now with both music and lyrics, and they have really influenced my writing in that they love easter eggs and creating intricate albums. I actually have a reference to one of their songs in a poem I wrote!

So a lot of the music I listen to has either given me ideas for poems or helped me to choose my words more carefully when writing. I used to write songs when I was in high school, so a lot of my poetry started as lyrics.

Furthermore, I don’t know how unconventional this is, but a HUGE influence for this book was actually Florence Welch from Florence + the Machine. She just released her own book of lyrics and poetry last summer, and it was a huge influence for me.

More than that, I remember reading up on some of her album concepts, and I always wished I could create a body of work that was so cohesive and intense as a Florence + the Machine album. I love how ethereal and strange Florence’s works are, and I really wanted to channel that in my own writing/story.

SH: You do a beautiful job of maintaining a narrative through your poems. How does this cohesive narrative differ from other collections of poetry, and was it a conscious choice you made when writing Water Runs Red?

JC: I’m so happy to hear that! It was the first big decision I made about the book actually. I have always been pretty frustrated that most modern poetry collections claim to be narrative driven, even going so far as to tell an overarching story within the book, but not really being a chronologically [or] cohesive story.

I wanted this book to be more like a novel-turned-poetry collection. Not necessarily a novel written in verse like The Poet X by Elizabeth Acevedo or an Ellen Hopkins book, but a poetry collection that had a defined narrative.

That was probably the hardest part of keeping this collection cohesive because I had three separate narratives running through the whole book, and I wanted it all in chronological order in a way that transitioned well between everything.

It took a lot of planning and editing and talking to beta-readers, and at one point last September, I actually printed out all 300 poems and laid them on my floor so I could manually move them and make sure everything worked.

I’m really pleased with how it worked out in the end because it does read like a story rather than a sporadic collection of poems thrown together. This was my way of writing a novel without actually having to write 100,000 words to do it.

SH: What do you hope your readers walk away with after reading Water Runs Red?

JC: We have to start changing things before it’s too late, and this was the only thing I could think to do to make my voice heard and to lift up the voices of those who need to be heard more than I do.

There’s a lot of crappy stuff happening to people today; there always has been, but ever since the 2016 [election], I feel like the darkness has been building, and through all of that, I wanted to give people hope. I wanted to light the fires within the people who may not be thinking about fighting.

More than anything, I want people to walk away from it thinking about the problems and possibilities in our world today. The book is primarily about my experiences about dealing with the darkness that surrounds us, but I wanted the hardest hitting part of the book to be that light conquers darkness.

And I know my book won’t change things—I know some of my more conservative relatives who read it may not understand the urgency in it, but I do know that it will cause people to think. It will force people to hear things that they hadn’t thought about before. It will allow people to see themselves in a new light, and if a reader can walk away thinking, “Wow the world really has to change,” that’s enough.