“Painting is silent poetry and poetry is painting that speaks” — greek philosopher, Plutarch

Writers have taken inspiration from famous paintings for decades, penning philosophical or personal musings on their experience with a piece of art. The technical term for such a poem is known as an ekphrastic poem. Poet Alfred Corn wrote an essay on the history of ekphrastic verse, stating “once the ambition of producing a complete and accurate description is put aside, a poem can provide new aspects for a work of visual art.” To showcase this, here are four poems inspired by influential or famous paintings.

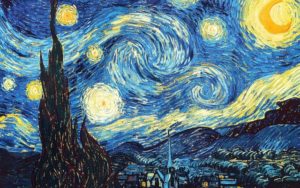

The Starry Night, Van Gogh, 1889

Inspired by Van Gogh’s painting of the same name, Anne Sexton uses the imagery of a desolate town under the night sky to express her longing for death and her desire to be overpowered by a force greater than oneself.

The Starry Night by Anne Sexton

The town does not exist

except where one black-haired tree slips

up like a drowned woman into the hot sky.

The town is silent. The night boils with eleven stars.

Oh starry starry night! This is how

I want to die.

It moves. They are all alive.

Even the moon bulges in its orange irons

to push children, like a god, from its eye.

The old unseen serpent swallows up the stars.

Oh starry starry night! This is how

I want to die:

into that rushing beast of the night,

sucked up by that great dragon, to split

from my life with no flag,

no belly,

no cry.

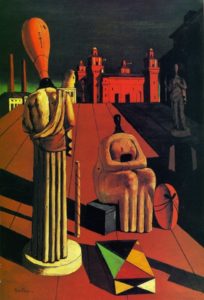

The Disquieting Muses, de Chirico, 1918

Sylvia Plath captures the unsettling mood of this de Chirico painting with her equally eerie poem, The Disquieting Muses. The speaker imagines her childhood self haunted by three faceless muses, much like the Three Fates of classical mythology. Like de Chirico’s painting, the blank faces “stand vigil” over her, casting their long shadows “in the setting sun / That never brightens or goes down”.

The Disquieting Muses by Sylvia Plath

Mother, mother, what ill-bred aunt

Or what disfigured and unsightly

Cousin did you so unwisely keep

Unasked to my christening, that she

Sent these ladies in her stead

With heads like darning-eggs to nod

And nod and nod at foot and head

And at the left side of my crib?

Mother, who made to order stories

Of Mixie Blackshort the heroic bear,

Mother, whose witches always, always,

Got baked into gingerbread, I wonder

Whether you saw them, whether you said

Words to rid me of those three ladies

Nodding by night around my bed,

Mouthless, eyeless, with stitched bald head.

In the hurricane, when father’s twelve

Study windows bellied in

Like bubbles about to break, you fed

My brother and me cookies and Ovaltine

And helped the two of us to choir:

“Thor is angry: boom boom boom!

Thor is angry: we don’t care!”

But those ladies broke the panes.

When on tiptoe the schoolgirls danced,

Blinking flashlights like fireflies

And singing the glowworm song, I could

Not lift a foot in the twinkle-dress

But, heavy-footed, stood aside

In the shadow cast by my dismal-headed

Godmothers, and you cried and cried:

And the shadow stretched, the lights went out.

Mother, you sent me to piano lessons

And praised my arabesques and trills

Although each teacher found my touch

Oddly wooden in spite of scales

And the hours of practicing, my ear

Tone-deaf and yes, unteachable.

I learned, I learned, I learned elsewhere,

From muses unhired by you, dear mother

I woke one day to see you, mother,

Floating above me in bluest air

On a green balloon bright with a million

Flowers and bluebirds that never were

Never, never, found anywhere.

But the little planet bobbed away

Like a soap-bubble as you called: Come here!

And I faced my traveling companions.,

Day now, night now, at head, side, feet,

They stand their vigil in gowns of stone,

Faces blank as the day I was born,

Their shadows long in the setting sun

That never brightens or goes down.

And this is the kingdom you bore me to,

Mother, mother. But no frown of mine

Will betray the company I keep.

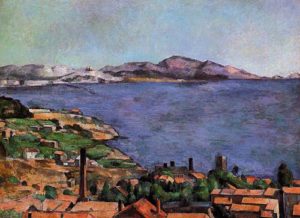

L’Estaque, Cézanne, 1883

In true poetry fashion, Allen Ginsberg uses his poem to look beyond Cézanne’s impressionist painting of L’Estaque, a fishing village just west of Marseille, and focuses on the transcendent reality that “doesn’t occur on the canvas”. “For the other side of the bay / is Heaven and Eternity” It’s interesting to see a front runner of the Beat generation take inspiration from a prominent figure in the impressionist art movement and make something new out of two groundbreaking mediums.

Cézanne’s Ports by Allen Ginsberg

In the foreground we see time and life

swept in a race

toward the left hand side of the picture

where shore meets shore.

But that meeting place

isn’t represented;

it doesn’t occur on the canvas.

For the other side of the bay

is Heaven and Eternity,

with a bleak white haze over its mountains.

And the immense water of L’Estaque is a go-between

for minute rowboats.

Diana and Actaeon, Titian, 1556-59

Titian’s painting depicts a scene between Diana and Actaeon from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. It shows the moment of accidental discovery as Actaeon, after a day’s hunting, spies the naked Diana bathing with her nymphs. As the story goes, Actaeon is then transformed into a stag and is chased and killed by his own dogs. Szirtes’s poem is told from the point of view of Actaeon. According to The Art Desk, the quote Szirities begins the poem with is “a quote from Donne’s Elegy XX (From His Mistress Going to Bed): “O My America, My Newfoundland”, which is a “tantalising play on sexual discovery and conquest.”

Actaeon by George Szirtes

O, my America, my Newfoundland

John Donne, “Elegy 20”

O, my America, discovered by slim chance,

behind, as it seemed, a washing line

I shoved aside without thinking –

does desire have thoughts or define

its object, consuming all in a glance?

You, with your several flesh sinking

upon itself in attitudes of hurt,

while the dogs at my heels

growl at the strange red shirt

under a horned moon, you, drinking

night water – tell me what the eye steals

or borrows. What can’t we let go

without protest? My own body turns

against me as I sense it grow

contrary. Whatever night reveals

is dangerously toothed. And so the body burns

as if torn by sheer profusion of skin

and cry. It wears its ragged dress

like something it once found comfort in,

the kind of comfort even a dog learns

by scent. So flesh falls away, ever less

human, like desire itself, though pain

still registers in the terrible balance

the mind seems so reluctant to retain,

o, my America, my nakedness!